It is official. Today at 8:57 a.m. it was empirically proven that there is no correlation between intelligence and the capital letters postdating one’s name. In the university setting and the world over there is a gross assumption that an individual’s smarts can be equated with the prestige of their major, profession, or number of degrees they hold. The majority of the people who believe this have the Ms, Ds, PHs, Js, and BAs after their names and send their children to college, perpetuating a self fulfilling societal farce that masks pedanticity as intelligence.

My appointment is at 8:15 a.m. Blood pressure, no pain, a solid temperature, (and) I am ushered into the exam room. Crappy cologne first, then the doctor himself; sporting a navy blue polo shirt with vertical rows of sailing flags, a detective’s moustache, and high school county championship ring he asks me if I am ready.

I am as ready as I am going to be.

He escorts me to another room where he confuses my right foot for my left foot several times, finally drooling iodine all over my ingrown toenail. Running before walking, he now puts on his exam gloves. Clumsily, he fills the syringe and proceeds to jab my foot six times, obviously unsure about what he is doing, like a toddler who struggles to play with a toy that is meant for a child three years older, a Looney Tunes character trying to blow out its tail.

His plastic hospital I.D. card shimmers on the counter: First Name, Last Name, M.D.

Twenty minutes and my toe is numb. Hunting for the scissors and gauze, he puts gloves on and does the procedure. At one point he yelps, “Wow! Look at all the pus,” the medical professional response to an infected wound. Gloves bloody, he pours through every cabinet in the room wiping blood on all the handles and some of the cabinet doors. My toe hurts but I pinch myself to make sure this is actually happening. A doctor wiping blood all over a room, surely sanitary and surely an 11-year-old knows not to do that.

He can’t find the bottle of alcohol he is looking for so picks up a can that is lying around. Holding it upside down he flips it in the air, displaying that he’s still got his high school finesse, reads it, chuckles, proud of himself, and squirts some white soap on my foot.

No, not actually empirical, but telling. This man has being practicing medicine for decades. He told me so. He has those prestigious, awe-inspiring initials after his name yet he is one of the least competent individuals I have ever met.

Coming off a week of orientation for incoming freshman where I met countless pre-med students, students who want to be lawyers and joint J.D./Ph.D.s, today was a harrowing experience that typifies a crippling lack of creativity within the adolescent/young professional mindset. Intellect, pursuit out of curiosity not a teleological, career obsessed, money making impetus for learning, is lost. Students care about their grades but not their minds. The majority of undergraduates obsess over internships, jobs, grades, and graduate school before they ask questions that might make them better writers, thinkers, or more holistic young adults. Such is the climate of college campuses today and it is blinding, rendering most students unable to function in non traditional capacities and non traditionally in professional careers. Able to pay for Kaplan and get into med school sure, but to think for themselves, take a risk, read a book that is not assigned or on Oprah’s book club, no. Worst of all, this literally mind-numbing set of expectations has become the norm – the laudable norm, the revered doctor, the brilliant lawyer, you must be smart of you have a PhD.

My toe knows better.

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Friday, August 4, 2006

Pretty Much The Coolest Thing Ever

Complete with soda, too much food, cake and extended family, the pomp of the birthday celebration August 1st was the same as any other I’ve been to but the circumstance was different. It wasn’t my birthday but it was the anniversary of the coolest thing that has ever happened to me. The coolest thing by far.

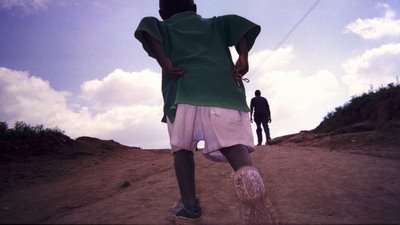

During the summer of ’05 I volunteered for an NGO in Kibera, one of the largest slums in Nairobi and East Africa. My project finished before the date of my departure so much of my time was dedicated to letting children pet my milky skin, spending time with people, and doing my best to lighten the mood whenever inappropriate. Up to nothing of note, the head of the organization summoned my volunteer title and volunteered me to paint the clinic. Situated within the slum, the clinic provides basic health care on a sliding scale for residents of the community and was in the process of formal registration in the hopes of getting free vaccines from the government. Regulations stipulated that the clinic be white.

Replete with a coverall, paint and brushes, turpentine, no clue, drop clothes, and a foot stool, I set to work. Unlike my jokes or vague development lingo painting the clinic was a tangible contribution. It made me feel good. The work I did in the clinic on August 1st, 2005, however, made me feel even better.

Hopped up on turpentine fumes, I was brushing away, a veritable painting machine -- the Arnold of slum clinic painting like you’d never believe. Most of the patients just stared at my like I was nuts. One patient was different, in far too much pain to notice the connect the dots pattern spackled on my face, eight centimeters preoccupied.

Another volunteer burst into my studio – there is going to be a baby she effervesced. Flashing back to the Miracle of Life video in Mr. Aptekar’s class my initial reaction was: eww. Another couple of minutes and I poked my head in to ask the nurse to ask the woman giving birth if it would be ok for me to sit in. She said yes. With the paint still on my face I gloved up, put on a white coat and did what I thought I was supposed to. “You are doing great momma,” I cooed in English to a Kswahili speaking woman in labor. She froze me with a look, “shut up boy, this is not a sitcom, this is number six and the last” curtly communicated her wrinkled face. My pit stains continued to grow.

I meant well but took the hint, content to hold her hand and wipe her forehead. With a strong push, there was another life in the world. In that moment, there was a presence in the room bigger than any individual – in the balance of the Earth, creation, destruction, life, death, I saw a child born. There was no conservation of mass in this equation. A new baby in the world, a new person. Slimy, gross and more beautiful than anything I have ever seen, the recently converted amphibian was handed to me. Thirteen seconds old. My hands were quaking. A new person in the world and I was holding him, before the mother, before the father, as he was taking his first breaths.

As the nurse focused on the mom, I focused on the baby wrapping him in a sweatshirt, cleaning him up, in awe. Newborn topped with a hat, the mother in recovery holding her new son, I was now up to effervescing, writing the word “baby” all over the walls of my masterpiece, a best attempt at trapping a the enormity what just happened.

At the end of the day, exhausted, I cleaned up, washed my hands, got dressed and went to thank the mother. Babbling in a mixture of English and almost Kswahili, I told her thank you, thank you, and thank you, my best attempt failing again, unsure of what really just happened but knowing I was forever indebted to her sharing his birth with me.

Asante sana, mother. I can’t thank you enough.

Your welcome, she said, in a tone of voice that told me how tired her soul was. HIV positive, like her husband, neither employed, there was now another mouth to feed.

What is his name?

She looked up at me, her eyes glowing, a smile more sincere than any I’ve ever seen, 'Baby Aaron.

--

August 1, 2006 was baby Aaron’s 1st birthday -- happy birthday baby Aaron.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Secular Missionaries And A Life Disconnected

Experiencing turbulence, I awoke startled. Tired, cramped, I was ready to land in Kenya but the map said we were just crossing over the Mediterranean. To my left snored a middle aged man wearing a black shirt with bold orange letters that read: Baptists for Botswana.

Missionaries speckle the Kenyan landscape, roaming in Range Rovers, rivaling the cheetah population, wild creatures in the own right as they bible thump their way into the slums proselytizing predatorily on the starving poor, poaching tribal traditions towards the brink of extinction. Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religion in the world. Kenya is a Christian country. Most mission work that is done in East Africa is headquartered in Nairobi, the largest city between Cape Town and Cairo, the control center for thousands of sentinels seeking to civilize the barbarians, redeem them in Christ.

The presence of Christian missionaries is undeniable, but it is easily eclipsed by the bigger cars, budgets, houses, egos, and bolder t-shirts of the secular missionaries that occupy the gated neighborhoods surrounding the city center. Forget cheetahs, we are the wildebeest. Like the religious work that is headquartered here, any news agency, NGO, micro credit scheme, fair trade organization, women’s empowerment group, or foundation has an East Africa office here. I am a disciple of the secular gospel, doling out condoms, pushing women’s rights, starting sustainable enterprise, empowering youth, in command of all the jargon, the development testaments new and old.

With a faith as strong as a Baptist for Botswana, I believe that the work I do is right, part of a larger plan that will help positively impact the lives of those same starving poor. I choose not to think of my work as predatory, but when I walk through Kibera on a Sunday and hear the sermons, revival meetings, and exorcisms my scoffing at religious mission work doesn’t make my white skin, my presence in the largest slum in East Africa, any less obnoxious. Neither condoms nor communion are helping in the long term.

Both sets of missionaries are equally culpable, both to blame for the problems that aren’t fixed, for living a lifestyle that is entirely disharmonious, prowling the slums by day, be it to convert or vaccinate, and eating $15 dollar meals by night before retreating to a gated compound. Doctrines aside, there is a common baseline that indicts missionaries of all belief systems. There are no simple solutions, and while both sides insist they are right and the other wrong, neither is consistent. Lifestyle is a choice. Inevitably, the most religious and the most secular, both passionate, live disconnected from the work they do, keeping them in business by driving, buying, living, socializing, drinking, sleeping, the system that causes the problems they work to solve.

Missionaries speckle the Kenyan landscape, roaming in Range Rovers, rivaling the cheetah population, wild creatures in the own right as they bible thump their way into the slums proselytizing predatorily on the starving poor, poaching tribal traditions towards the brink of extinction. Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religion in the world. Kenya is a Christian country. Most mission work that is done in East Africa is headquartered in Nairobi, the largest city between Cape Town and Cairo, the control center for thousands of sentinels seeking to civilize the barbarians, redeem them in Christ.

The presence of Christian missionaries is undeniable, but it is easily eclipsed by the bigger cars, budgets, houses, egos, and bolder t-shirts of the secular missionaries that occupy the gated neighborhoods surrounding the city center. Forget cheetahs, we are the wildebeest. Like the religious work that is headquartered here, any news agency, NGO, micro credit scheme, fair trade organization, women’s empowerment group, or foundation has an East Africa office here. I am a disciple of the secular gospel, doling out condoms, pushing women’s rights, starting sustainable enterprise, empowering youth, in command of all the jargon, the development testaments new and old.

With a faith as strong as a Baptist for Botswana, I believe that the work I do is right, part of a larger plan that will help positively impact the lives of those same starving poor. I choose not to think of my work as predatory, but when I walk through Kibera on a Sunday and hear the sermons, revival meetings, and exorcisms my scoffing at religious mission work doesn’t make my white skin, my presence in the largest slum in East Africa, any less obnoxious. Neither condoms nor communion are helping in the long term.

Both sets of missionaries are equally culpable, both to blame for the problems that aren’t fixed, for living a lifestyle that is entirely disharmonious, prowling the slums by day, be it to convert or vaccinate, and eating $15 dollar meals by night before retreating to a gated compound. Doctrines aside, there is a common baseline that indicts missionaries of all belief systems. There are no simple solutions, and while both sides insist they are right and the other wrong, neither is consistent. Lifestyle is a choice. Inevitably, the most religious and the most secular, both passionate, live disconnected from the work they do, keeping them in business by driving, buying, living, socializing, drinking, sleeping, the system that causes the problems they work to solve.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

As the sun rises over Kibera, a balmy mist lingers backlighting exhales, putting second-hand wool hats on. Dew forms on the cocotenies [wheelbarrows] while the men who sleep in them fight the sun for five more minutes of slumber, five more minutes of procrastination from the day labor that might mean eating but definitely means sleeping well. Cool is typical for July in the slum but not the typical vision of Kenya, trading lion postcards for wet paths and shade for jackets.

George Ngeta emerges as the dew retreats. It is cold, but this is home. With an unflappable calm, he stretches, concerned less with the cold and more with the to-do list in his head. Checking it twice, he knows who is nice but refuses to give up on the naughty. Cold suits him. Development literature often babbles on about being of the community, participatory development, tapping indigenous knowledge sets. Usually, there is some talk of thinking outside of the box, of leveling the playing field between Western and Third. Deliberately vague terms or the ideas behind them, despite best efforts, are not working; Ngeta is the creativity that exists within the cracks of ambiguous phrases, the Kris Kringle of development, far out of the box, what is working, a touch of the Fourth world, the North Pole of sustainable enterprise.

Ngeta’s mind didn’t always reside in the North Pole. Born in Western Province, like most people in Kibera, he came looking for excitement but called it work. Luckily, he found work at a hotel cleaning toilets. Stomaching the smell, aware of the hordes of young people flocking to the city, he scrubbed away, humming as he still does today. One night he filled in for the no show DJ, birthing DJ George. Seduced by bright lights and bumping baselines, nightlife consumed him. So too did the less pleasant aspects. After a while, the danger of Nairobi’s nightlife dulled the shine of discos. It wasn’t worth it. In time, he found his reindeer in social work, guiding him to do the work that he does today.

He has been poor, out of work, hungry, drunk. He doesn’t know what it means to be hopeless. His smile communicates his unrelenting optimism.

Sprawling in the shadows of Nairobi’s waning skyline, nobody actually knows Kibera’s population. Except Ngeta. He knows everyone. He knows that there are 822, 328 people in the bordering villages. He would know, constantly bringing them good wishes, sincere hellos, and parcels of distraction. Cause enough for hope. Shaking dreams from his bones he dresses. A hooded sweatshirt, grey and black cap, jeans, and durable shoes. 320KSH in his pocket, he sets out for the day. Grizzly, he hasn’t shaved in a week. He never brings a pen but always needs one. On his left hand around his ring finger prides his luster-free wedding band. Rested upon his melon belly, his hands are clasped with a disarming confidence, raised only to greet. Walking to his workshop ought to take 15 minutes but takes 40. Humming with the blaring reggae from the aging radio in the barber shop, Ngeta takes the time to greet each person as he passes them, “Habari Mami” he coos at the woman frying mandazi, “Niaje Mdos” he defers to the elder fundi, “Sasa!” he intonates at the bundled baby. It is cold, but without asking he knows what his neighbors need, naughty or nice, stopping to show you care, a smile and a greeting warm the soul.

George Ngeta emerges as the dew retreats. It is cold, but this is home. With an unflappable calm, he stretches, concerned less with the cold and more with the to-do list in his head. Checking it twice, he knows who is nice but refuses to give up on the naughty. Cold suits him. Development literature often babbles on about being of the community, participatory development, tapping indigenous knowledge sets. Usually, there is some talk of thinking outside of the box, of leveling the playing field between Western and Third. Deliberately vague terms or the ideas behind them, despite best efforts, are not working; Ngeta is the creativity that exists within the cracks of ambiguous phrases, the Kris Kringle of development, far out of the box, what is working, a touch of the Fourth world, the North Pole of sustainable enterprise.

Ngeta’s mind didn’t always reside in the North Pole. Born in Western Province, like most people in Kibera, he came looking for excitement but called it work. Luckily, he found work at a hotel cleaning toilets. Stomaching the smell, aware of the hordes of young people flocking to the city, he scrubbed away, humming as he still does today. One night he filled in for the no show DJ, birthing DJ George. Seduced by bright lights and bumping baselines, nightlife consumed him. So too did the less pleasant aspects. After a while, the danger of Nairobi’s nightlife dulled the shine of discos. It wasn’t worth it. In time, he found his reindeer in social work, guiding him to do the work that he does today.

He has been poor, out of work, hungry, drunk. He doesn’t know what it means to be hopeless. His smile communicates his unrelenting optimism.

Sprawling in the shadows of Nairobi’s waning skyline, nobody actually knows Kibera’s population. Except Ngeta. He knows everyone. He knows that there are 822, 328 people in the bordering villages. He would know, constantly bringing them good wishes, sincere hellos, and parcels of distraction. Cause enough for hope. Shaking dreams from his bones he dresses. A hooded sweatshirt, grey and black cap, jeans, and durable shoes. 320KSH in his pocket, he sets out for the day. Grizzly, he hasn’t shaved in a week. He never brings a pen but always needs one. On his left hand around his ring finger prides his luster-free wedding band. Rested upon his melon belly, his hands are clasped with a disarming confidence, raised only to greet. Walking to his workshop ought to take 15 minutes but takes 40. Humming with the blaring reggae from the aging radio in the barber shop, Ngeta takes the time to greet each person as he passes them, “Habari Mami” he coos at the woman frying mandazi, “Niaje Mdos” he defers to the elder fundi, “Sasa!” he intonates at the bundled baby. It is cold, but without asking he knows what his neighbors need, naughty or nice, stopping to show you care, a smile and a greeting warm the soul.

Monday, July 3, 2006

Can't you see that it's just raining, Jack Johnson croons, there ain't not need to go outside. Solitaire bores me and his word-drawn pictures of infatuation take my mind to women past, the gap between love and the idea of love, and the drought in my love life. Drought in my sex life. It hasn't rained in a while.

Clicking and tapping, the sounds of the keyboard and rain on the window sing the harmony meant to accompany the song and my interior monologue. I feel sorry for myself, lonely, and wanting. It is companionship I lack. I want someone to reassure me, not to ask but know what's bothering me, beauty like a Marquez sentence, a reason not to go outside. Like the weather, these thoughts are always present and always changing, sunny and hopeful some days, cloudy and melancholy others. Today my mood is grey, waxing pathetic in step with the guitar rhythm. It seems natural. I have come to expect these bouts of loneliness. I've not grown taller in a couple of years but these tempestuous horizons seem right, post-pubescent growing pains of a 21-year-old in a foreign land, unsure of who to trust, what to believe, wishing there was an easy answer, someone to console him in a primal way, quelling the anxiety that constantly spreads with the mechanical regularity of his beating heart.

All this from the rain.

More than anything, the sad rain pines on about the importance of detail. Perfect companionship that flourishes on the details of the counterpart. Partners who complement, make happy, communicate with their eyes, know through their touch, trigger inside jokes with random words, love through living. Indeed, it is the small things. Small things that I think I miss because of the mood I summon from the rain highlight the screaming disconnect between my reactions and realities, a gaping hole between my fairytale life and truth in front of me. My reactions to small things are the most obvious indicators of ignorance. Large signs, Welcome to Nairobi, seeing poverty, hearing Kiswahili, speaking with Kenyans, tell me I am in Kenya but the small things tell me that I am in a real place, a different place, a country, city and slum that is not an entry in the Lonely Planet or coordinate location on a map but a contrasting reality. Something as massive and amorphous as poverty, a slum of ~1 million, are thoughts that loom larger than logic. Palpable yes, different certainly, harrowing and unforgettable but easily ignored because poverty is so impersonal, too massive, untouchable, entirely unfounded within most Westerner's database of reactions. So it is the small things that make it real. Contrasting reactions to the exact same things allow me to understand that I really don't understand. Poverty is too big, but I know what reactions are triggered by rain and a grey day. Prompted by the small things, my reactions are telling of the extent to which my mind is simply conditioned differently. It rains and I pine while tomorrow the mud paths will be impassable. Sex-life; companionship; these romantic notions of what life ought to be are in and of themselves different realities in my mind than they are for most Kenyans. Moreover, the rain, a natural event, a small thing, a common occurrence worldwide, means something so different to me in my head than it does in life here.

Sheets now. A crowd gathers below the canopy at the entrance to our compound. Miles, not just a window, gate, electrical fence, guard dog, are wedged between me and the people I see reaching for umbrellas, jogging for shelter, covering new hair dos. Running for shelter, rushing to get home, stay dry, stay clean, stay warm, most of the people I look down on don't look so different from a crowd in midtown when the skies open. But, chances are their reactions are different. Frolicking in the rain is only fun when you know you can warm up afterwards. It is even more fun when warming up is an assumption. A warm shower, a dry home, a cup of tea made with clean water, inviting clothing. People in Kibera don’t chase rainbows.

What does the rain mean to you if you live in a structure made of mud, don’t have running water, an extra pair of shoes, or paved road to your house. What does the rain mean to you if you can't open your business, or your child will get sick? What does the rain mean if it is your drinking water?

I don’t know. It is probably not a prompt to feel pathetic in the confines of your warm home. I don’t know. That is the whole point. The small things point out: I have no idea.

Clicking and tapping, the sounds of the keyboard and rain on the window sing the harmony meant to accompany the song and my interior monologue. I feel sorry for myself, lonely, and wanting. It is companionship I lack. I want someone to reassure me, not to ask but know what's bothering me, beauty like a Marquez sentence, a reason not to go outside. Like the weather, these thoughts are always present and always changing, sunny and hopeful some days, cloudy and melancholy others. Today my mood is grey, waxing pathetic in step with the guitar rhythm. It seems natural. I have come to expect these bouts of loneliness. I've not grown taller in a couple of years but these tempestuous horizons seem right, post-pubescent growing pains of a 21-year-old in a foreign land, unsure of who to trust, what to believe, wishing there was an easy answer, someone to console him in a primal way, quelling the anxiety that constantly spreads with the mechanical regularity of his beating heart.

All this from the rain.

More than anything, the sad rain pines on about the importance of detail. Perfect companionship that flourishes on the details of the counterpart. Partners who complement, make happy, communicate with their eyes, know through their touch, trigger inside jokes with random words, love through living. Indeed, it is the small things. Small things that I think I miss because of the mood I summon from the rain highlight the screaming disconnect between my reactions and realities, a gaping hole between my fairytale life and truth in front of me. My reactions to small things are the most obvious indicators of ignorance. Large signs, Welcome to Nairobi, seeing poverty, hearing Kiswahili, speaking with Kenyans, tell me I am in Kenya but the small things tell me that I am in a real place, a different place, a country, city and slum that is not an entry in the Lonely Planet or coordinate location on a map but a contrasting reality. Something as massive and amorphous as poverty, a slum of ~1 million, are thoughts that loom larger than logic. Palpable yes, different certainly, harrowing and unforgettable but easily ignored because poverty is so impersonal, too massive, untouchable, entirely unfounded within most Westerner's database of reactions. So it is the small things that make it real. Contrasting reactions to the exact same things allow me to understand that I really don't understand. Poverty is too big, but I know what reactions are triggered by rain and a grey day. Prompted by the small things, my reactions are telling of the extent to which my mind is simply conditioned differently. It rains and I pine while tomorrow the mud paths will be impassable. Sex-life; companionship; these romantic notions of what life ought to be are in and of themselves different realities in my mind than they are for most Kenyans. Moreover, the rain, a natural event, a small thing, a common occurrence worldwide, means something so different to me in my head than it does in life here.

Sheets now. A crowd gathers below the canopy at the entrance to our compound. Miles, not just a window, gate, electrical fence, guard dog, are wedged between me and the people I see reaching for umbrellas, jogging for shelter, covering new hair dos. Running for shelter, rushing to get home, stay dry, stay clean, stay warm, most of the people I look down on don't look so different from a crowd in midtown when the skies open. But, chances are their reactions are different. Frolicking in the rain is only fun when you know you can warm up afterwards. It is even more fun when warming up is an assumption. A warm shower, a dry home, a cup of tea made with clean water, inviting clothing. People in Kibera don’t chase rainbows.

What does the rain mean to you if you live in a structure made of mud, don’t have running water, an extra pair of shoes, or paved road to your house. What does the rain mean to you if you can't open your business, or your child will get sick? What does the rain mean if it is your drinking water?

I don’t know. It is probably not a prompt to feel pathetic in the confines of your warm home. I don’t know. That is the whole point. The small things point out: I have no idea.

Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Before I left for Kenya last summer, Carolina for Kibera, Inc. gave me a 15-page release listing, in great detail, all the dangers of Nairobbery. Yesterday was a hard day.

One of the things that they stress the most is understanding that as a white person working in a slum you are, to some degree or another, a target. Money is associated with you. So, you need to anticipate what your reaction would be if you were to get robbed. Less about being the hero or not – don’t be the hero, give up your money, phone, camera etc. – the question is: Do you make a scene?

That liability release form has half-a-page on mob justice. Yesterday was a hard day; Mob justice is real.

If a thief is found, a mob of people beat the shit out of him, most times until he is dead. No trial, no first amendment, no Miranda cards, no qualms. Don’t steal and if you get robbed don’t say anything. That is the lesson from yesterday.

We had a great training in the morning with one of the smarter, less organized youth groups. They are sharp and see right through our handouts. What are SCJ products going to do rats the size of cats? No answer. Their questions, criticism, and interaction are good though. They make me think again and again about what I am doing but I also know that if this is ever going to work it is only going to work when the youth groups tear the protocol to pieces, take what they think is good, and make it their own. Our discussion is lively, we stress the need to be as creative as possible when approaching these issues, and do an in-home training, pointing out the main places to look for pest infestation, how to relate to the customer, safety procedures etc.

A great training. I am not sure that this group is ready to start but they are just as ready or not ready as any of the other groups. At this point one year after the initial idea generation workshop it is time to start, understand what works, what doesn’t, and what we can do to make it better.

On the way out the rabid guard dogs scare me a little, but I am in a good mood. Muddy and stank, the path from the house dips and snakes out to the main drag where right away the tension is tangible. What the fuck, I think, what is going on?

My face is obviously not relaxed, and the guy next to me, a member of the youth group no older than 18 leans to me, without any sense of violence, calm and ordinary, “mob violence.”

Just another day in Kibera really, nothing new. Mob justice, that’s all.

We walk around the crowd that is jam-packed 5-deep in a neat circle around the thief. Men stand above him, panting, with a look on their face expressing a life worth of frustration. Each day, each month and each year, for most of the people in Kibera is a life of injustice. Systematic exploitation, a gross disregard for human life, for the poor, for people who just don’t matter enough, screams from the muscles of their clenched jaws. Beating that man means not biting your tongue, not being ignored, not being the victim again and again of the world’s injustice. Cathartic and rare, mob justice seems to be a community coping exercise.

Walking by, the bloody man’s eyes dart around like a cornered rodent. He has nowhere to go. He just looks relieved that the beating has stopped - momentarily. Some whispers - those other people should not have intervened on his behalf. If they hadn’t, he would be dead. Sirens grow closer. Police arrive as we walk on. His beating is prevented momentarily. When he gets in that car or to the cell he will get it. He is not dead.

Yesterday was a hard day.

Racing, confused, and relieved, my mind tries to make sense of what just happened. No, it can’t just yet. Before a processing session, we walk by a grown man crawling on all fours. He is postured over a pile of ash. Garbage isn’t collected in the slums so people burn it. Meticulously raking through the ash that is no longer garbage he picks out bones and makes a smaller pile off to the side. Carefully, he breaks each one open looking for marrow.

I wonder what I would do if someone robbed me. That wonder doesn’t last long. My mind doesn’t actual understand that last 2 minutes. I wouldn’t do anything. Take it, just take it.

One of the things that they stress the most is understanding that as a white person working in a slum you are, to some degree or another, a target. Money is associated with you. So, you need to anticipate what your reaction would be if you were to get robbed. Less about being the hero or not – don’t be the hero, give up your money, phone, camera etc. – the question is: Do you make a scene?

That liability release form has half-a-page on mob justice. Yesterday was a hard day; Mob justice is real.

If a thief is found, a mob of people beat the shit out of him, most times until he is dead. No trial, no first amendment, no Miranda cards, no qualms. Don’t steal and if you get robbed don’t say anything. That is the lesson from yesterday.

We had a great training in the morning with one of the smarter, less organized youth groups. They are sharp and see right through our handouts. What are SCJ products going to do rats the size of cats? No answer. Their questions, criticism, and interaction are good though. They make me think again and again about what I am doing but I also know that if this is ever going to work it is only going to work when the youth groups tear the protocol to pieces, take what they think is good, and make it their own. Our discussion is lively, we stress the need to be as creative as possible when approaching these issues, and do an in-home training, pointing out the main places to look for pest infestation, how to relate to the customer, safety procedures etc.

A great training. I am not sure that this group is ready to start but they are just as ready or not ready as any of the other groups. At this point one year after the initial idea generation workshop it is time to start, understand what works, what doesn’t, and what we can do to make it better.

On the way out the rabid guard dogs scare me a little, but I am in a good mood. Muddy and stank, the path from the house dips and snakes out to the main drag where right away the tension is tangible. What the fuck, I think, what is going on?

My face is obviously not relaxed, and the guy next to me, a member of the youth group no older than 18 leans to me, without any sense of violence, calm and ordinary, “mob violence.”

Just another day in Kibera really, nothing new. Mob justice, that’s all.

We walk around the crowd that is jam-packed 5-deep in a neat circle around the thief. Men stand above him, panting, with a look on their face expressing a life worth of frustration. Each day, each month and each year, for most of the people in Kibera is a life of injustice. Systematic exploitation, a gross disregard for human life, for the poor, for people who just don’t matter enough, screams from the muscles of their clenched jaws. Beating that man means not biting your tongue, not being ignored, not being the victim again and again of the world’s injustice. Cathartic and rare, mob justice seems to be a community coping exercise.

Walking by, the bloody man’s eyes dart around like a cornered rodent. He has nowhere to go. He just looks relieved that the beating has stopped - momentarily. Some whispers - those other people should not have intervened on his behalf. If they hadn’t, he would be dead. Sirens grow closer. Police arrive as we walk on. His beating is prevented momentarily. When he gets in that car or to the cell he will get it. He is not dead.

Yesterday was a hard day.

Racing, confused, and relieved, my mind tries to make sense of what just happened. No, it can’t just yet. Before a processing session, we walk by a grown man crawling on all fours. He is postured over a pile of ash. Garbage isn’t collected in the slums so people burn it. Meticulously raking through the ash that is no longer garbage he picks out bones and makes a smaller pile off to the side. Carefully, he breaks each one open looking for marrow.

I wonder what I would do if someone robbed me. That wonder doesn’t last long. My mind doesn’t actual understand that last 2 minutes. I wouldn’t do anything. Take it, just take it.

Friday, June 23, 2006

Stars shine and I miss my comfort zone. Five- beers-pensive and an electrical black out, Counting Crows whine and my thoughts this summer have never been more cogent. Cutting through the bullshit, smog, language barriers it is obvious, present always and unavoidable: my life here exists behind bars, fences, gates, locks, and security systems. The biggest barrier is the internally programed security system: my ability to rationalize, validate, and reason life hour by hour in an attempt to avoid digesting reality because of the bad taste it might leave on my life, wanting to paint in shades of grey, constructing things how they are not. There is no grey. Black and white. Me and Kenya. People in Kibera live in their own shit.

My "work" this summer exists withing a rigid, meant-to-guide-but-confused framework. Development, the undergraduate do gooder, liberal white democrat, priveleged and Base of Pyramid Protocol paradigms collude to stir me in circles, round and round between believing in what I am doing - that what I am doing is good - and being totally overwhelmed by the enormity of it all, the skills I don't have, and that truth that the world just does not care about the poor. It is easier not to but those paradigms have pointed me in a caring direction, without true guidance, just suggestions about what I ought to do, should feel, uphold as important; so, I want to care. The question is, how much do I really care. What does caring actually mean. Since when has caring ever made a difference. It is not about me. A better question is: What is it going to take? There are no more secrets about disease, the world's poor, dirty drinking water, kids dying all the time - the normalcy of death for the majority of the world and the lack of understanding by the controling minority.

"A,"my emails read, "it is going to take more people like you." I am not convinced.

Electricity in our apartment is out. It happens all the time. So what - there are no consequences. Each day I do what I want, take it seriously, choose to do "good" and when the thought of what happens next enters my mind, images inevitably lead to graduation, fun this Fall and the family and friends I miss - never do I think, for example, of what I might eat next. If I do, I think about it because I would love an ice cream sundae. Malaria meds, diarrhea pills and multi vitamins are swallowed without an afterthought. If I get sick - so what? I can get medicine. I am a tall white male with money. What if I get really sick. I can go home where I can get world-class treatment in a hospital that gives preferential treatment to the upper middle class. Just put that ticket on my credit card. So, so what. Some people in Kibera have no electricity. Every day in the world 40,000 people die of preventable diseases. World cup fever sweeps the world while diarhea kills children. That pint, jersey, and match ticket is enough to vaccinate villages.

"A, don't be so hard on yourself," emails from the U.S. read.

As we were walking today I said to Vivian, I hope we are not those people that mean well but just fuck things up even further, setting up expectations but only creating more need. A classic aid/development mistake.

"A, you mean well," my emails read.

Since when has meaning well ever made a difference.

Thanks to a generous per diem and sweet funding from SCJ, we live in a beautiful apartment complex - swimming pool, sauna, steam room, my own bathroom, 24-hour security. Make a left out of our compound, walk 15 minutes and you arrive on the outer rim of Kibera - one of the largest informal settlements/slums in the world. On our way home from the office we walk out of the nicest part of Kibera, past the bus station and heckling matatu touts, turn left at the car wash where the women are cat called the sweet smell of burning garbage at Christo Church wafts by, my boogers are black, hang a right at the huge puddle, surely a mosquito favorite, into the market. Welcome, Karibu, Myzoungou how are you, suspicous stares, fleeting glances, blaring music, burning oil, and the odor of human shit blend together to create a backdrop for my darting eyes. I have been told the market can be dangerous. My sunglasses provide just another layer. My life exists behind bars. Dark sunglasses or not, I try not to wear my confusion on my face. Layer upon layer of conditioned thinking, media reports, electrical fences, barb wire, complexion, studies, studies that study studies, combine to block my way not through the market but through making sense of anything, never fully allowing my guard down, trained too well to empathize just enough. My sun burned face is the most honest, telling aspect of my life here - a natural, unconcious reflection of how embarrased I really feel. An ethos of blushing. Apologizing for not being able to stand up to the same sun, the same smells, the same drinking water, the same earth shelters, the same lack of medicine. Red and sorry, sorry for my inability, hoping that I am not one of the people that books are written about because they just fuck things up but blushing nonetheless because no matter how I try or what my intenions are, I just have no idea if what I am doing or if what I am doing will have any impact on anyone whatsoever.

"A," one email reads, "such is the nature of this work"

Musty market paths give way to diesel fumes as we get out to the street. Mammas hawk their veggies. When we buy prodcue we buy from the mothers, thinking it good that we give our money to the local women and not the supermarket chain. Shifting sand really. I'm a little re, a little embarrased by the 5 minute quest I put this merchant through in search of change for my 500 shilling note. Twenty shilling mango in hand, I cringe at the buchery, judge the psychos at the pentacostal church blaring exorcisms over their PA system, eye the t-shirt seller up ahead. A quick glance is all I give, keeping my face disinterested, hiding behind the opaque lenses that mask whatever fear might be screaming in my eyes. Forget Greenpoint, these are the thrift store items hipsters scour eBay for. I want to buy a cool t shirt that I can wear to a bar in the Fall. A great chat piece no doubt. "Where did you get that shirt, she might ask" In Kenya. Wow what were you doing in Kenya. Cue the monologue about slum work, Kibera, and life there. Cue the empathetic smile. Cue the comment about what the money I used to buy my beer could buy there and watch her walk away. A little too wierd. Old books, hats, socks, more hats, mangoes, sausages, sugarcane, white range rovers with whiter people, suits, trousers, bras, boxer shorts, a Massai, jewlery made of camel bone that is actually plastic, sneakers, all color my conusumer pallet beckoning with an air of trendy flair as I make the left up Ngong Road. Right then a City Hoppa bus downshifts and belches a plume of black diesel smoke, masacring my lungs. If you could have an asthma like a heart attack, by now I would have had 68 asthmas. Four men saunter by in pressed suits, olive, tan, black, and blue - well dressed, shoulders back, proud. Olive suits dont look good on me. Apex court, the place I stayed last visit is on my right, but I dont stop because Jane is probably at work and I dont care to see her. It would be nice I am sure but I just had another asthma and my heavy bookbag is making my back sweat like an old man playing basketball at the Y. Careful not to fall over the uneven paths, I make the right, walk up the street and greet the guards. They know me, but it usually doesnt matter - I am white and they like their job. Guards rarely stop me. Up the stairs, through the door. I am home. Safe behind a gate, the guards, the electric fence, my ability rationalize, facts, figures, money, white skin, light hair, dark sunglasses, conditioned responses, no sense of consequence, and constant reassurances from people that the work I am doing is good.

Bed time.

When I wake up, I am just as confused, restless, discontent. I do not know what to do. What is it going to take? I know only one thing, it is going to take a lot more than me.

What is it going to take?

I read the New York Times. An article reads:

In less than a decade, an estimated four million people have died, mostly of hunger and disease caused by the fighting. It has been the deadliest conflict since World War II, with more than 1,000 people still dying each day. For many here, survival, not elections, is the milestone.

Surviving for me is not an issue. I mean well but live behind bars. What is it going to take?

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

(the following article was written for Boiling Point Magazine and will be published in the April 2006 issue)

In Kenya men hold hands. Boys, teens, young men, married men, and grandfathers all hold hands as a term of endearment, not just to cross the street. Sexual orientation and holding hands are not related. Some of the most ‘manly’ men, men who might believe homosexuality is a sin, hold hands. Ignorance is bliss when thinking of physical affection between two guys, it is simply not a symptom of sexual orientation. At first, seeing this is a refreshing change from an unrelentingly homophobic American culture that links any form of physical affection between men as ‘gay,’ as not manly. Picture it: two men, chests out, heads high, laughing through a market on the busiest day of the week, hands locked. No weird glances, no fleeting glowers of disapproval. Now picture that in America, two power suits and big knots on bold colored ties in a financial district of a big city at rush hour, hands locked. It is hard to imagine the picture without imagining the looks, expressing feelings from discomfort to disgust. But make no mistake, Kenya, as a nation, is not comfortable with the any of the letters in the LQBTQ conversation. Initially settling, the fact the sexuality is never questioned, on second thought, becomes unsettling. It is assumed that no man would be gay.

In Kenya, sodomy is still a crime and men are still prosecuted for it. In 1998, the notoriously corrupt and ruthless Kenyan president Daniel arap Moi was quoted as saying, "Kenya has no room or time for homosexuals and lesbians." In a country where Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religion, there is an enormous conservative Christian presence that preaches homosexuality as a sin. A lot of those same manly men hold hands on their way to church. Regardless of where they are going, Kenya is not a LGBTQ-friendly country.

My time in Scotland has proved different. An equally, if not more, Christian country, it seems that religion has less flex here, overwhelmed by a relatively liberal public. Religion aside, homosexuality is far more talked about and accepted. My gay co-worker wears a wedding band and talks of his fiancé; they are to be married and afforded all the civil rights that a married man and woman would be given. People make fun of him because he wears tapered pants, but in this instance it is the inverse of Kenya. People in Scotland make ‘gay’ jokes as pejoratives but the foundations for acceptance and equality for people of all sexual preferences is poured and set in society. Of all places I have been, Scotland is the most likely to see those same men in suits with their hands clasped and not bat an eye. Incendiary debate raged leading up to the ratification of The Civil Partnership Act in December of 2005, but out of conflict has come progress. As a nation, Scotland is as sexually ecumenical as I have been to.

Yet, my time in Kenya and Scotland is not sufficient to draw absolute conclusions about national opinion. Such questions have no definitive answers, what do people really think about homosexuality? LGBTQ persons? Why is there an assumed discomfort and where does that discomfort come from? How is it remedied? Indeed, as Scotland has always known but recently confronted, and any queer person in Kenya would tell you, these are not easy questions. For heterosexual members of the world these questions are easily dismissed – they are not a daily reality. As Karen Booth, associate professor of Women's Studies and openly queer faculty member of the sexual studies minor at UNC, admits: “I do feel vulnerable to being dismissed, discounted, and despised when I come out to students and other members of Carolina's community.”

So a question that does deal directly with each of us resounds: Where does UNC stand when it comes to the acceptance of LGBTQ persons? Are some of those same men who think homosexuality is a sin sitting next to you in class?

An uncomfortable question for some, but it is exactly this discomfort that needs to be addressed because those awkward moments result in learning. When asked if he thought there was a fear of homosexuals on campus, former Student Body President Seth Dearmin conceded that there was work to do make campus more welcoming but, “I think we offer a very safe and friendly environmentfor all.” Dearmin’s concession is as telling as his statement. As accepting and diverse a place as UNC is, there is an undeniable discomfort with all students who are different. It is a visceral discomfort, hard to locate, or blame one person for, but difference is disquieting and often leads to fear. “Often times if they are afraid,” says Dr. Cecil Wooten, professor of classics, “they are afraid of differences. People, especially those who are unsure of themselves, often feel uncomfortable around people who are different. “

Enter education. Members of the LGBTQ community are not at Carolina to serve as a tool for education; they struggle, like all people who are discrimated against, for fair and equal treatment from everyone, institutions and people alike. But their struggle must not be pushed to the fringes; it should be embraced. The ‘eww’ faces at kiss-ins in the Pit that teach the lasting life lessons. This teaching must take place on two levels: peer-to-peer and university-wide. Fear of homosexuals, the perceived different, “could be remedied to a degree by frequent reminders from the administration of the University's non-discrimination policy; more funding of the LGBT office and of sexuality studies; more courses on LGBT issues; mandatory "safe zone" and anti-harassment workshops; the granting of health and other benefits to same sex partners of faculty, staff, and students,” says Karen Booth. Support from the University is essential, because it must, as an institution spearhead the fight against all discrimination and hatred on campus.

When asked the same question on combating fear of homosexuals, Dr. Wooten made an equally salient point: “I have never known anyone who knew a gay person who was afraid of gay people.” People to person, the myths are shattered.. As part of their education, students must be forced from their comfort zones by the University - the LGBTQ office helps facilitate these teaching moments - but they must also realize that growing up consists of challenging oneself. Carolina is not high school, it is time to begin thinking for yourself, critically, and realize that whatever the Bible might say, whatever your ignorance has allowed you believe up to the that point, is insufficient. A fear of the different, of LGBTQ persons does not withstand face-to-face interactions and all students need to be pushed and push themselves to be challenged.

This is not an easy thing to do but it is a necessary and important task as important as an A on a creative writing paper or biology final. Dr. Wooten asks: “Isn’t the removal of unreasonable fears and prejudices one of the functions of education?”

In Kenya men hold hands. Boys, teens, young men, married men, and grandfathers all hold hands as a term of endearment, not just to cross the street. Sexual orientation and holding hands are not related. Some of the most ‘manly’ men, men who might believe homosexuality is a sin, hold hands. Ignorance is bliss when thinking of physical affection between two guys, it is simply not a symptom of sexual orientation. At first, seeing this is a refreshing change from an unrelentingly homophobic American culture that links any form of physical affection between men as ‘gay,’ as not manly. Picture it: two men, chests out, heads high, laughing through a market on the busiest day of the week, hands locked. No weird glances, no fleeting glowers of disapproval. Now picture that in America, two power suits and big knots on bold colored ties in a financial district of a big city at rush hour, hands locked. It is hard to imagine the picture without imagining the looks, expressing feelings from discomfort to disgust. But make no mistake, Kenya, as a nation, is not comfortable with the any of the letters in the LQBTQ conversation. Initially settling, the fact the sexuality is never questioned, on second thought, becomes unsettling. It is assumed that no man would be gay.

In Kenya, sodomy is still a crime and men are still prosecuted for it. In 1998, the notoriously corrupt and ruthless Kenyan president Daniel arap Moi was quoted as saying, "Kenya has no room or time for homosexuals and lesbians." In a country where Pentecostalism is the fastest growing religion, there is an enormous conservative Christian presence that preaches homosexuality as a sin. A lot of those same manly men hold hands on their way to church. Regardless of where they are going, Kenya is not a LGBTQ-friendly country.

My time in Scotland has proved different. An equally, if not more, Christian country, it seems that religion has less flex here, overwhelmed by a relatively liberal public. Religion aside, homosexuality is far more talked about and accepted. My gay co-worker wears a wedding band and talks of his fiancé; they are to be married and afforded all the civil rights that a married man and woman would be given. People make fun of him because he wears tapered pants, but in this instance it is the inverse of Kenya. People in Scotland make ‘gay’ jokes as pejoratives but the foundations for acceptance and equality for people of all sexual preferences is poured and set in society. Of all places I have been, Scotland is the most likely to see those same men in suits with their hands clasped and not bat an eye. Incendiary debate raged leading up to the ratification of The Civil Partnership Act in December of 2005, but out of conflict has come progress. As a nation, Scotland is as sexually ecumenical as I have been to.

Yet, my time in Kenya and Scotland is not sufficient to draw absolute conclusions about national opinion. Such questions have no definitive answers, what do people really think about homosexuality? LGBTQ persons? Why is there an assumed discomfort and where does that discomfort come from? How is it remedied? Indeed, as Scotland has always known but recently confronted, and any queer person in Kenya would tell you, these are not easy questions. For heterosexual members of the world these questions are easily dismissed – they are not a daily reality. As Karen Booth, associate professor of Women's Studies and openly queer faculty member of the sexual studies minor at UNC, admits: “I do feel vulnerable to being dismissed, discounted, and despised when I come out to students and other members of Carolina's community.”

So a question that does deal directly with each of us resounds: Where does UNC stand when it comes to the acceptance of LGBTQ persons? Are some of those same men who think homosexuality is a sin sitting next to you in class?

An uncomfortable question for some, but it is exactly this discomfort that needs to be addressed because those awkward moments result in learning. When asked if he thought there was a fear of homosexuals on campus, former Student Body President Seth Dearmin conceded that there was work to do make campus more welcoming but, “I think we offer a very safe and friendly environmentfor all.” Dearmin’s concession is as telling as his statement. As accepting and diverse a place as UNC is, there is an undeniable discomfort with all students who are different. It is a visceral discomfort, hard to locate, or blame one person for, but difference is disquieting and often leads to fear. “Often times if they are afraid,” says Dr. Cecil Wooten, professor of classics, “they are afraid of differences. People, especially those who are unsure of themselves, often feel uncomfortable around people who are different. “

Enter education. Members of the LGBTQ community are not at Carolina to serve as a tool for education; they struggle, like all people who are discrimated against, for fair and equal treatment from everyone, institutions and people alike. But their struggle must not be pushed to the fringes; it should be embraced. The ‘eww’ faces at kiss-ins in the Pit that teach the lasting life lessons. This teaching must take place on two levels: peer-to-peer and university-wide. Fear of homosexuals, the perceived different, “could be remedied to a degree by frequent reminders from the administration of the University's non-discrimination policy; more funding of the LGBT office and of sexuality studies; more courses on LGBT issues; mandatory "safe zone" and anti-harassment workshops; the granting of health and other benefits to same sex partners of faculty, staff, and students,” says Karen Booth. Support from the University is essential, because it must, as an institution spearhead the fight against all discrimination and hatred on campus.

When asked the same question on combating fear of homosexuals, Dr. Wooten made an equally salient point: “I have never known anyone who knew a gay person who was afraid of gay people.” People to person, the myths are shattered.. As part of their education, students must be forced from their comfort zones by the University - the LGBTQ office helps facilitate these teaching moments - but they must also realize that growing up consists of challenging oneself. Carolina is not high school, it is time to begin thinking for yourself, critically, and realize that whatever the Bible might say, whatever your ignorance has allowed you believe up to the that point, is insufficient. A fear of the different, of LGBTQ persons does not withstand face-to-face interactions and all students need to be pushed and push themselves to be challenged.

This is not an easy thing to do but it is a necessary and important task as important as an A on a creative writing paper or biology final. Dr. Wooten asks: “Isn’t the removal of unreasonable fears and prejudices one of the functions of education?”

social graces

How was your break?

“Shut up,” I reply. Well, not actually, I say it in my head

I’ve been back in St. Andrews for a week now and every time I get asked that question I cant stand it; this is me maturing.

It is like the scripted conversation you have when you first meet someone. Hi. What’s your name? Where are you from? Where do you go to school? What do you study? Do you know ________? By the time you get to the second question you have already forgotten the persons name and make some stupid excuse like “Oh I am so bad with names” Insert an awkward laugh. The next time you see that same person, who might know the kid you sat next to in 7th grade, haven’t spoken to in 10 years but heard goes to the same school, you introduce a friend, whose name you do know, with the hopes that they learn the unnamed acquaintance’s name.

Growing up I was taught to be open-minded, not to ‘judge a book by its cover’ and accept all people. However, in my young adulthood I’m finding that some books aren’t worth reading. You need to decide that just by looking at their covers. Some people just suck, are not fun or interesting, and there is no problem in brushing them off – I am going to forget your name anyway. For the sake of the really good people out there, the ones worth reading, you must be discerning with the ways you spend your time and with whom you spend it.

That’s why Hong Kong kicked ass. One girl asked Alex if he was gay because he chose to hang out with Jon and me instead of her, two guys with comparatively not- pert bosoms. He laughed and we went drinking. His actions are telling of a certain level of maturity. How you spend your time, whom you invest in and develop friendships with is so important. If you think someone sucks, don’t spend time with them. There is nothing wrong with that. It is a good thing.

Alex, Jon, and I explored the city, went out, played basketball, and just chilled doing what we wanted when we wanted, making fun of each other as we went, telling stories from both freshman years. When playing basketball is was obvious we know each other better than we sometimes know ourselves. Alex knew I was going to use my left hand before I had dribbled and Jon knew I was going to spin before Alex checked it. Jon was red after two beers; Alex and I were still thirsty. Walking down the crowded street shoulder to shoulder loud and obnoxious, talkative but perceptive, there were no fake conversations. It was time well spent with two of the guys who consider my parents their friends, will be my mates for the rest of my life, probably buy my underage kids beer, and tell stories at my wedding. There were other guys on their programs, and yes of course there were women (although they weren’t entirely sure what to make of me, a gangly 6’3” bearded white guy with a beast of hair on his head) but so what… the truth is, those people just don’t matter that much to me.

Of course there is this idea of social grace, being a nice person, a sociable character, and there is nothing wrong with that. But, when knowing other people or seeking to be cool somehow validates who you are, you need to consider your motivations. St. Andrews is a university predicated on social networks, authenticating people by what societies they are in, who they know, what golf score they shoot, how much money their parents make and what animal they have emblazoned on their polo shirts. Never have I been in a place where there is larger concern with outward appearance and the class you convey. Worst of all, most people are unsure if they think it is okay or not, entirely unclear as whether being a blue blooded aristocrat is for them enviable or worth flaunting, so they spinelessly play to their audience, content to cognac with the old boys one day and deride them behind their back another. Consistency is rare, boiling down to an insecure sense of self. Somehow, if I can know a lot of people, not even know there names, but have many friends I wave to in the street, I am more complete.

To these people I think, “Shut up.” You don’t care how my break was and knowing people doesn’t validate me. I don’t mind the fact that I find the books on my shelf more exciting than the people here. And while that is not entirely fair because of course I haven’t met everyone. I know I have good friends and am just as content not have superficial heartless conversations.

Each person needs to figure out how they want to read other people, what are they going to look for, who is worth you time, who is going to make you laugh, challenge you, force you to grow, be at your wedding? It is vital to make good friends and keep those friends around you. For different people, there is different criterion. I have mine and I don’t feel bad about it. I am still a nice person, but I am a nice person who knows how he wants to spend his time. Being opinionated is not bad. Call me anti-social, a hermit, abrasive, standoffish or get more colourful with your adjectives. It doesn’t bother me.

This is me maturing.

“Shut up,” I reply. Well, not actually, I say it in my head

I’ve been back in St. Andrews for a week now and every time I get asked that question I cant stand it; this is me maturing.

It is like the scripted conversation you have when you first meet someone. Hi. What’s your name? Where are you from? Where do you go to school? What do you study? Do you know ________? By the time you get to the second question you have already forgotten the persons name and make some stupid excuse like “Oh I am so bad with names” Insert an awkward laugh. The next time you see that same person, who might know the kid you sat next to in 7th grade, haven’t spoken to in 10 years but heard goes to the same school, you introduce a friend, whose name you do know, with the hopes that they learn the unnamed acquaintance’s name.

Growing up I was taught to be open-minded, not to ‘judge a book by its cover’ and accept all people. However, in my young adulthood I’m finding that some books aren’t worth reading. You need to decide that just by looking at their covers. Some people just suck, are not fun or interesting, and there is no problem in brushing them off – I am going to forget your name anyway. For the sake of the really good people out there, the ones worth reading, you must be discerning with the ways you spend your time and with whom you spend it.

That’s why Hong Kong kicked ass. One girl asked Alex if he was gay because he chose to hang out with Jon and me instead of her, two guys with comparatively not- pert bosoms. He laughed and we went drinking. His actions are telling of a certain level of maturity. How you spend your time, whom you invest in and develop friendships with is so important. If you think someone sucks, don’t spend time with them. There is nothing wrong with that. It is a good thing.

Alex, Jon, and I explored the city, went out, played basketball, and just chilled doing what we wanted when we wanted, making fun of each other as we went, telling stories from both freshman years. When playing basketball is was obvious we know each other better than we sometimes know ourselves. Alex knew I was going to use my left hand before I had dribbled and Jon knew I was going to spin before Alex checked it. Jon was red after two beers; Alex and I were still thirsty. Walking down the crowded street shoulder to shoulder loud and obnoxious, talkative but perceptive, there were no fake conversations. It was time well spent with two of the guys who consider my parents their friends, will be my mates for the rest of my life, probably buy my underage kids beer, and tell stories at my wedding. There were other guys on their programs, and yes of course there were women (although they weren’t entirely sure what to make of me, a gangly 6’3” bearded white guy with a beast of hair on his head) but so what… the truth is, those people just don’t matter that much to me.

Of course there is this idea of social grace, being a nice person, a sociable character, and there is nothing wrong with that. But, when knowing other people or seeking to be cool somehow validates who you are, you need to consider your motivations. St. Andrews is a university predicated on social networks, authenticating people by what societies they are in, who they know, what golf score they shoot, how much money their parents make and what animal they have emblazoned on their polo shirts. Never have I been in a place where there is larger concern with outward appearance and the class you convey. Worst of all, most people are unsure if they think it is okay or not, entirely unclear as whether being a blue blooded aristocrat is for them enviable or worth flaunting, so they spinelessly play to their audience, content to cognac with the old boys one day and deride them behind their back another. Consistency is rare, boiling down to an insecure sense of self. Somehow, if I can know a lot of people, not even know there names, but have many friends I wave to in the street, I am more complete.

To these people I think, “Shut up.” You don’t care how my break was and knowing people doesn’t validate me. I don’t mind the fact that I find the books on my shelf more exciting than the people here. And while that is not entirely fair because of course I haven’t met everyone. I know I have good friends and am just as content not have superficial heartless conversations.

Each person needs to figure out how they want to read other people, what are they going to look for, who is worth you time, who is going to make you laugh, challenge you, force you to grow, be at your wedding? It is vital to make good friends and keep those friends around you. For different people, there is different criterion. I have mine and I don’t feel bad about it. I am still a nice person, but I am a nice person who knows how he wants to spend his time. Being opinionated is not bad. Call me anti-social, a hermit, abrasive, standoffish or get more colourful with your adjectives. It doesn’t bother me.

This is me maturing.

Sunday, April 9, 2006

A sleepless night's thoughts on Hong Kong

Jetlag is one of those words that people use a lot, but I don’t really know what it means. Likewise, my body doesn’t know what time it is. I didn’t sleep last night. Each time I closed my eyes images of Hong Kong danced on my eyelids, Chinese characters kept me from sleeping, flitting around, each to their own beat, rhythmically obeying their respective tones, inflecting different meaning with each subtle step across the dome of my eye. I remain enchanted.

Despite being from New York City, the greatest city in the world, Hong Kong makes little sense to me. Nine days is only nine days and I didn’t expect to leave with definite conclusions, but my reactions are more confused than I anticipated. New York hardly seems like the city that never sleeps; not only does Hong Kong not sleep, it doesn’t appear to rest.

Meeting Jon at the airport was the sweet reunion I had anticipated, an old friend who, at times, knows me better than I know myself, our common history readily apparent from our first step in the same direction – goofy body language, obnoxious volume to our voice, painfully obvious stares at passing women, a random jump shot and an undeniable camaraderie that is founded in time spent together. Yet it was weird seeing him in Hong Kong. I know Jon is Chinese. His last name is Chan, I take my shoes off before I go into his house, and his parents have told me their stories of immigration. Doi, Jon is Chinese. But never before did he look so white. This struggle to unite with a culture that he identifies with but feels he does not own was apparent in his face. In showing me around, he wanted to speak Chinese and facilitate an experience as authentic as possible, but he has just a hard a time facilitating it for himself as he does for me, a gangly white guy a head taller than everyone in the crowd. I drowned in my cultural illiteracy, content to rely on Chinese speakers for help and to stand out on the train. Jon struggles to swim in a culture his eyes and last name indicate are his own, but western mind and language skills tell him otherwise.

I do stand out in the train. I really stand out. No matter the time of the day, if the train is open it is crowded. Like the streets, there are always people packed around you bustling somewhere, children, bags, partners, and trendy shopping bags in tow. Each train is divided into cars, but doors do not separate the cars so you can see from the head of the snake to the tail, watching it wend its way through the well-planned underground. It is evident that the subway has been planned flawlessly, moving millions of people throughout the day without breaking a sweat. It is a good thing for me because the last thing I want to do is look at a map with a blank stare drawing more attention to myself. I am the only not-Chinese person in sight. I stand where the snakes stomach would be, can see both ends, and it really is true, I am the only non-Chinese person in sight. My head is cocked slightly to the right, clearing the ceiling by no more than four inches as the stale train air is exhausted on my neck. In that moment, I feel like Gulliver, landed in a foreign place where I am unlike anyone around me.

But, I am not attacked, tied down, or stared at. As I gaze around the train, I realize that no one gazes back. People chat on their cell phones, kids play with their parents, the guys in suits look uptight and stressed, the little grandmas look so adorable – I want to scoop one up and pinch her wrinkled little cheeks – teens negotiate their sexual tension through awkward touches and suggestive stares; I don’t stop anyone from doing what they normally do. People don’t care that I am standing there. So what, there’s a big white guy standing in the train. They notice me, but their attention is nothing more than a fleeting glance, more concerned about what stop they need to get off at, what’s for dinner, or the woman’s cleavage on the other side of the car.

My feeling of being out of place is entirely self-imposed, a creation of my mind, a narcissistic obsession to think that my skin color might be of consequence to people. It is almost as if I want people to gawk at me, but they have better things to do than worry about some almost-bearded American with smelly armpits. That being said, it answered a question that so often is raised in discussions on race: Why do all the black kids sit together? With each stop I look around the car to see of any people who are not Chinese get on the train. I won’t know them and probably won’t talk to them but there will be an undeniable moment of eye-contact solidarity between any non-Chinese person and me. I know that the Chinese people don’t care; I too am preoccupied with that woman’s cleavage, but I seek that empathy in the eyes of people who I think are like me. Constructed and contrived, I still feel out of place and yurn for my comfort zone.

Ironically enough, it is only the look that I seek from the other non-Chinese people on the train, in the street, or at a bar; I don’t actually care to know them because I can see we look alike, but I hope so badly that we are not actually alike. During my stay there is a massive rugby tournament on, The Sevens, and the bars, clubs, and streets are overrun with Western tourists hoped up on imported beer and sunburns. With all of me, I hope I don’t look like them, pathetic white people in Hong Kong to get drunk and watch rugby, a real change from a British pub – good thing they took an 11-hour flight to do it. Chop sticks? Yea right, may I have a fork. They don’t say please, they don’t say thank you, and they don’t really care about being in Hong Kong. The neon signs make for a good photo, the Filipina prostitute makes for a good story and the cheap Carlsberg makes for a good drunk. They flaunt their money and say hi to their queen on the back of the coins, imposing their culture with their obnoxious ethos, sweating an air of cultural superiority that has never left the island, it has only spread to the other western countries. American exchange students don’t know who the woman on the back of the 100 dollar bills is, but are just as happy to spend them at Happy Hour.

I look the same, but want so badly to be received differently, as a person attune to cultural distinctions, foods, and languages. I want people to know that I respect them, that I am not just another obnoxious guy along for a good time. I will use chop sticks – I swear. But, I use them poorly, and no matter how badly I want to deny it, reject it, or admit it, to a certain degree I am just another white guy.

Western influence looms large in Hong Kong, not just in the arrogant approach of foreigners who couldn’t care less about anything Chinese. It is hard to walk more than two blocks without seeing a 7-11. Louis Vuitton, Mark Jacobs, Ralph Lauren, Armani, Lacoste, Fendi, Chanel, and Burberry are just a few of the stores that dominate opulent malls across the city. Capitalism, implemented and perpetuated on western terms has become part of Hong Kong. In these stores the salesmen and women are Chinese, but their English grammar is better than mine, their clothes were designed in France and made in a factory in China, but the label is flaunted with a classist air that stinks of neo-colonialism. The irony is stupid. Hong Kong is hardly independent.

Many of the malls and high-end shops are housed in the lobbies of Hong Kong’s famed skyscrapers. HSBC, The Bank of America, Standard Charter, and The Bank of China, to name a few, rise over the island, imposing their presence in an unmistakable way. They finance the Western-planted consumer cult that infects Hong Kong. Their buildings dance each night in the world-famous light show but these lights also blind the picture-taking tourists from the harrowing reality – Hong Kong island has been methodically stripped of its culture. The people look different, but they don’t care that I am there. There is nothing new about me, the West has been here for a long time, the presence has become natural and people continue to buy it.

--

Yet I remain enchanted by a city that looks, tastes, smells and most defiantly sounds unlike anything I know. What a complex place, full of so many different vibrant people. Of course my conclusions about the ghosts of colonialism and western influence are premature. I think also, partly right. But, more than anything, they are wholly insufficient. I still don’t understand that city, the language, the people, or the customs; each is too beautiful and complex, but I delight in trying.

My trip was not an anti-Western diatribe. It was two of the best weeks of my life, complementing a new city with great friends, laughing the entire time.

Despite being from New York City, the greatest city in the world, Hong Kong makes little sense to me. Nine days is only nine days and I didn’t expect to leave with definite conclusions, but my reactions are more confused than I anticipated. New York hardly seems like the city that never sleeps; not only does Hong Kong not sleep, it doesn’t appear to rest.