Before I left for Kenya last summer, Carolina for Kibera, Inc. gave me a 15-page release listing, in great detail, all the dangers of Nairobbery. Yesterday was a hard day.

One of the things that they stress the most is understanding that as a white person working in a slum you are, to some degree or another, a target. Money is associated with you. So, you need to anticipate what your reaction would be if you were to get robbed. Less about being the hero or not – don’t be the hero, give up your money, phone, camera etc. – the question is: Do you make a scene?

That liability release form has half-a-page on mob justice. Yesterday was a hard day; Mob justice is real.

If a thief is found, a mob of people beat the shit out of him, most times until he is dead. No trial, no first amendment, no Miranda cards, no qualms. Don’t steal and if you get robbed don’t say anything. That is the lesson from yesterday.

We had a great training in the morning with one of the smarter, less organized youth groups. They are sharp and see right through our handouts. What are SCJ products going to do rats the size of cats? No answer. Their questions, criticism, and interaction are good though. They make me think again and again about what I am doing but I also know that if this is ever going to work it is only going to work when the youth groups tear the protocol to pieces, take what they think is good, and make it their own. Our discussion is lively, we stress the need to be as creative as possible when approaching these issues, and do an in-home training, pointing out the main places to look for pest infestation, how to relate to the customer, safety procedures etc.

A great training. I am not sure that this group is ready to start but they are just as ready or not ready as any of the other groups. At this point one year after the initial idea generation workshop it is time to start, understand what works, what doesn’t, and what we can do to make it better.

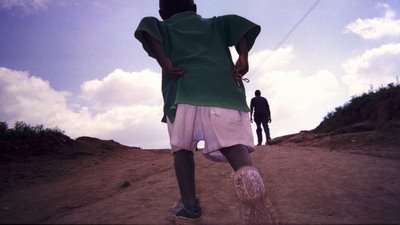

On the way out the rabid guard dogs scare me a little, but I am in a good mood. Muddy and stank, the path from the house dips and snakes out to the main drag where right away the tension is tangible. What the fuck, I think, what is going on?

My face is obviously not relaxed, and the guy next to me, a member of the youth group no older than 18 leans to me, without any sense of violence, calm and ordinary, “mob violence.”

Just another day in Kibera really, nothing new. Mob justice, that’s all.

We walk around the crowd that is jam-packed 5-deep in a neat circle around the thief. Men stand above him, panting, with a look on their face expressing a life worth of frustration. Each day, each month and each year, for most of the people in Kibera is a life of injustice. Systematic exploitation, a gross disregard for human life, for the poor, for people who just don’t matter enough, screams from the muscles of their clenched jaws. Beating that man means not biting your tongue, not being ignored, not being the victim again and again of the world’s injustice. Cathartic and rare, mob justice seems to be a community coping exercise.

Walking by, the bloody man’s eyes dart around like a cornered rodent. He has nowhere to go. He just looks relieved that the beating has stopped - momentarily. Some whispers - those other people should not have intervened on his behalf. If they hadn’t, he would be dead. Sirens grow closer. Police arrive as we walk on. His beating is prevented momentarily. When he gets in that car or to the cell he will get it. He is not dead.

Yesterday was a hard day.

Racing, confused, and relieved, my mind tries to make sense of what just happened. No, it can’t just yet. Before a processing session, we walk by a grown man crawling on all fours. He is postured over a pile of ash. Garbage isn’t collected in the slums so people burn it. Meticulously raking through the ash that is no longer garbage he picks out bones and makes a smaller pile off to the side. Carefully, he breaks each one open looking for marrow.

I wonder what I would do if someone robbed me. That wonder doesn’t last long. My mind doesn’t actual understand that last 2 minutes. I wouldn’t do anything. Take it, just take it.

Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Friday, June 23, 2006

Stars shine and I miss my comfort zone. Five- beers-pensive and an electrical black out, Counting Crows whine and my thoughts this summer have never been more cogent. Cutting through the bullshit, smog, language barriers it is obvious, present always and unavoidable: my life here exists behind bars, fences, gates, locks, and security systems. The biggest barrier is the internally programed security system: my ability to rationalize, validate, and reason life hour by hour in an attempt to avoid digesting reality because of the bad taste it might leave on my life, wanting to paint in shades of grey, constructing things how they are not. There is no grey. Black and white. Me and Kenya. People in Kibera live in their own shit.

My "work" this summer exists withing a rigid, meant-to-guide-but-confused framework. Development, the undergraduate do gooder, liberal white democrat, priveleged and Base of Pyramid Protocol paradigms collude to stir me in circles, round and round between believing in what I am doing - that what I am doing is good - and being totally overwhelmed by the enormity of it all, the skills I don't have, and that truth that the world just does not care about the poor. It is easier not to but those paradigms have pointed me in a caring direction, without true guidance, just suggestions about what I ought to do, should feel, uphold as important; so, I want to care. The question is, how much do I really care. What does caring actually mean. Since when has caring ever made a difference. It is not about me. A better question is: What is it going to take? There are no more secrets about disease, the world's poor, dirty drinking water, kids dying all the time - the normalcy of death for the majority of the world and the lack of understanding by the controling minority.

"A,"my emails read, "it is going to take more people like you." I am not convinced.

Electricity in our apartment is out. It happens all the time. So what - there are no consequences. Each day I do what I want, take it seriously, choose to do "good" and when the thought of what happens next enters my mind, images inevitably lead to graduation, fun this Fall and the family and friends I miss - never do I think, for example, of what I might eat next. If I do, I think about it because I would love an ice cream sundae. Malaria meds, diarrhea pills and multi vitamins are swallowed without an afterthought. If I get sick - so what? I can get medicine. I am a tall white male with money. What if I get really sick. I can go home where I can get world-class treatment in a hospital that gives preferential treatment to the upper middle class. Just put that ticket on my credit card. So, so what. Some people in Kibera have no electricity. Every day in the world 40,000 people die of preventable diseases. World cup fever sweeps the world while diarhea kills children. That pint, jersey, and match ticket is enough to vaccinate villages.

"A, don't be so hard on yourself," emails from the U.S. read.

As we were walking today I said to Vivian, I hope we are not those people that mean well but just fuck things up even further, setting up expectations but only creating more need. A classic aid/development mistake.

"A, you mean well," my emails read.

Since when has meaning well ever made a difference.

Thanks to a generous per diem and sweet funding from SCJ, we live in a beautiful apartment complex - swimming pool, sauna, steam room, my own bathroom, 24-hour security. Make a left out of our compound, walk 15 minutes and you arrive on the outer rim of Kibera - one of the largest informal settlements/slums in the world. On our way home from the office we walk out of the nicest part of Kibera, past the bus station and heckling matatu touts, turn left at the car wash where the women are cat called the sweet smell of burning garbage at Christo Church wafts by, my boogers are black, hang a right at the huge puddle, surely a mosquito favorite, into the market. Welcome, Karibu, Myzoungou how are you, suspicous stares, fleeting glances, blaring music, burning oil, and the odor of human shit blend together to create a backdrop for my darting eyes. I have been told the market can be dangerous. My sunglasses provide just another layer. My life exists behind bars. Dark sunglasses or not, I try not to wear my confusion on my face. Layer upon layer of conditioned thinking, media reports, electrical fences, barb wire, complexion, studies, studies that study studies, combine to block my way not through the market but through making sense of anything, never fully allowing my guard down, trained too well to empathize just enough. My sun burned face is the most honest, telling aspect of my life here - a natural, unconcious reflection of how embarrased I really feel. An ethos of blushing. Apologizing for not being able to stand up to the same sun, the same smells, the same drinking water, the same earth shelters, the same lack of medicine. Red and sorry, sorry for my inability, hoping that I am not one of the people that books are written about because they just fuck things up but blushing nonetheless because no matter how I try or what my intenions are, I just have no idea if what I am doing or if what I am doing will have any impact on anyone whatsoever.

"A," one email reads, "such is the nature of this work"

Musty market paths give way to diesel fumes as we get out to the street. Mammas hawk their veggies. When we buy prodcue we buy from the mothers, thinking it good that we give our money to the local women and not the supermarket chain. Shifting sand really. I'm a little re, a little embarrased by the 5 minute quest I put this merchant through in search of change for my 500 shilling note. Twenty shilling mango in hand, I cringe at the buchery, judge the psychos at the pentacostal church blaring exorcisms over their PA system, eye the t-shirt seller up ahead. A quick glance is all I give, keeping my face disinterested, hiding behind the opaque lenses that mask whatever fear might be screaming in my eyes. Forget Greenpoint, these are the thrift store items hipsters scour eBay for. I want to buy a cool t shirt that I can wear to a bar in the Fall. A great chat piece no doubt. "Where did you get that shirt, she might ask" In Kenya. Wow what were you doing in Kenya. Cue the monologue about slum work, Kibera, and life there. Cue the empathetic smile. Cue the comment about what the money I used to buy my beer could buy there and watch her walk away. A little too wierd. Old books, hats, socks, more hats, mangoes, sausages, sugarcane, white range rovers with whiter people, suits, trousers, bras, boxer shorts, a Massai, jewlery made of camel bone that is actually plastic, sneakers, all color my conusumer pallet beckoning with an air of trendy flair as I make the left up Ngong Road. Right then a City Hoppa bus downshifts and belches a plume of black diesel smoke, masacring my lungs. If you could have an asthma like a heart attack, by now I would have had 68 asthmas. Four men saunter by in pressed suits, olive, tan, black, and blue - well dressed, shoulders back, proud. Olive suits dont look good on me. Apex court, the place I stayed last visit is on my right, but I dont stop because Jane is probably at work and I dont care to see her. It would be nice I am sure but I just had another asthma and my heavy bookbag is making my back sweat like an old man playing basketball at the Y. Careful not to fall over the uneven paths, I make the right, walk up the street and greet the guards. They know me, but it usually doesnt matter - I am white and they like their job. Guards rarely stop me. Up the stairs, through the door. I am home. Safe behind a gate, the guards, the electric fence, my ability rationalize, facts, figures, money, white skin, light hair, dark sunglasses, conditioned responses, no sense of consequence, and constant reassurances from people that the work I am doing is good.

Bed time.

When I wake up, I am just as confused, restless, discontent. I do not know what to do. What is it going to take? I know only one thing, it is going to take a lot more than me.

What is it going to take?

I read the New York Times. An article reads:

In less than a decade, an estimated four million people have died, mostly of hunger and disease caused by the fighting. It has been the deadliest conflict since World War II, with more than 1,000 people still dying each day. For many here, survival, not elections, is the milestone.

Surviving for me is not an issue. I mean well but live behind bars. What is it going to take?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)